Eric Williams, who in 1949 published a fictionalised account of his ingenious escape from Stalag Luft III’s East Compound along with Michael Codner and Oliver Philpot, penned the screenplay of The Wooden Horse, based on his novel. The 1950 release was not the first British cinematic treatment of the captivity theme but it is certainly one of the earliest and better known. I won’t bother providing a plot synopsis, and I am not even going to stick faithfully to the narrative order of the film. If you haven’t read the book and want to know what happens, just read the Wikipedia entry at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Wooden_Horse.

While this is not a review, I will mention that, of the five POW films I have viewed—Stalag 17 (1953) The Colditz Story (1955), Danger Within (1959), and The Great Escape (1963)—The Wooden Horse is my least favourite. For a story which has much natural drama and tension—will the Germans discover the tunnel? Will the kriegies execute a successful escape?—I found this rendition quite dull. Certainly, it displayed typical British restraint in its presentation and storytelling, and it was very slow. Perhaps I have been spoiled by modern heart-thumping thrillers where the agonisingly excruciating tension build-up is emphasised by a powerful score. Here, music is strangely absent as a device to heighten dramatic tension, and my pulse hardly fluttered above its normally languid state. But despite my personal taste for paced-up narratives, the slow tempo appropriately mirrors the plodding monotony of POW life.

Lifted from the film, courtesy of my trusty little 21st century version of the box brownie.

Regardless of the limp impression it made on me as entertainment, The Wooden Horse was Britain’s third most popular film in 1950. I don’t know what the Australian box office was like but it was well received. The Catholic Weekly appreciated the ‘high adventure’ of a story told with ‘restraint and conviction’. (The Catholic Weekly, 14 June 1951.) Adelaide’s News considered it a ‘good, honest, thrilling adventure story, filmed without any fancy tricks of technique (News, 23 February 1951). Launceston’s Examiner deemed it a ‘good British film’ with an ‘exciting, true story of the most remarkable POW escape’ (Examiner, 11 November 1950) and Melbourne’s Advocate considered it a ‘thoroughly good film’. Indeed, ‘the suspense is appalling’ with ‘a thousand chances of a slip leading to detection’. All in all, the Advocate declared, it was a film you ‘simply must see’. (Advocate, 25 October 1951.)

Despite the enthusiastic response, it left at least one contemporary Australian reviewer with mixed feelings. While praising the excellent cast, noting that it was ‘a highly entertaining film and a moving record of an escape from a German prison camp’, conceding that there were ‘some tense moments and from the commencement of the tunnelling the film grips’, and recommending the film as ‘arresting … and one well worth seeing’, The Newcastle Sun’s reviewer considered that ‘it fails to impress as a film of such nature should’. The Sun helpfully speculated that the fault could have been in the way the men and captivity was presented. ‘Instead of capturing … that feeling of despair and utter longing to break free, the producers have made it seem that Stalag Luft was a happy place with very humane German guards.’ (The Newcastle Sun, 16 June 1951.) Not only do these men have guards who can be subverted through bribery and coercion, they also have a benign commandant. Explaining off the call for vaulting volunteers, the Senior British Officer tells the Kommandant, ‘Gym class, you know’. ‘Always this craze for exercise’, responded the Kommandant, as he unwittingly allowed plans for the wooden horse to progress.

Leeton’s The Murrumbidgee Irrigator, however, gained a different impression of prison life. Their reviewer considered that the film highlighted the ‘living death’ of life ‘behind the wire entanglements (The Murrumbidgee Irrigator, 10 July 1941) while The Catholic Weekly recognised the ‘boredom and frustration of active men immobilised’ and considered that the ‘narrative quietly brings out the remarkable ingenuity and resourcefulness of the prisoners in coping with the limitations of their situation’. (The Catholic Weekly, 14 June 1951.)

One group of men considered the film a ‘must see’. On 2 October 1951, nineteen former Stalag Luft III kriegies—some who had not seem each other since liberation, and including Senator Justin O’Byrne who had flown in from Tasmania especially—trekked along to Hoyts in Melbourne for a reunion dinner and a screening of the film.

Justin O'Byrne

In doing so, they revealed an Australian connection to the wooden horse escape. According to Roberts Dunstan of the Melbourne Herald (3 October 1951), Jock McKechnie, who turned his carpentry skills to making seating and stage props for the East Compound theatre, also helped make the vaulting horse—his hands still bore the scars from the crude tools he had to use—and Bryce Watson slept in Eric Williams’ bed to cover his absence on the night of the escape.

Jock McKechnie

The film and reunion provided a good excuse to talk about old times, both the good, the bad, and the humorous and, when they were presented with a souvenir copy of Eric Williams’ book, Tony Gordon had his signed by all his former friends, and kept that memento all his life.

Tony Gordon

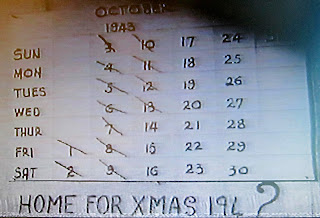

The Herald is silent on what these men thought of the film but I am sure that many scenes resonated, such as crossing off the days on the calendar—‘home for Xmas 194?’.

Lifted from the film, courtesy of my trusty little 21st century version of the box brownie.

Certainly, Hoyts’ special guests would have appreciated the many examples of kriegie ingenuity depicted in the film, especially, perhaps, Tony Gordon, who gained a reputation in his room as a ‘tin basher’, someone who could make anything out of next to nothing. He appears in the East Compound history for his work with metal and in the North Compound history for repairing and constructing secret radios.

Lifted from the film, courtesy of my trusty little 21st century version of the box brownie.

The film, which is set in Stalag Luft III’s East Compound in the summer of 1943, opens with some instructive text: ‘It is the constant hope of nearly every prisoner of war—if not, indeed, his duty—to escape and rejoin his unit.’ This establishes a rationale for why so many men willingly helped the escapers. Indeed, it was obvious from the beginning that the Wooden Horse effort would only ever see a handful of men escape, and only by the apparent good grace and selfless participation of the many. But why?

Lifted from the film, courtesy of my trusty little 21st century version of the box brownie.

Bert Comber

Peter Tunstall, who was not in Stalag Luft III but who was an inveterate escaper, recalled attending a lecture by Great War escape expert Squadron Leader AJ Evans: ‘the third thing really stuck with me. It was, he said, the duty of a prisoner of war “to be as big a bloody nuisance as possible to the enemy”. Those were his actual words. It seemed a pretty unequivocal instruction and I never forgot it.’ (Peter Tunstall: The Last Escaper, p. 106)

I have collected many examples of the captive airman’s belief in his duty to escape and, even if Thou Shalt Escape was not specifically one of the Airman’s Ten Commandments, there was certainly a belief that they would have to answer to their actions or inactions as prisoners when they were liberated. Indeed, King’s Regulations required that ‘a court of enquiry … be convened in every case [where an officer or airman had been taken prisoner] to investigate the conduct of the individual concerned and the circumstance of his capture’. But, as the war progressed, given the numbers of aircrew who found themselves ‘in the bag’, the Royal Air Force accepted that King’s Regulation 1324 had become ‘an impractical counsel of perfection’ and decided that no court of enquiry would be needed if the air officer commanding “was satisfied that no blame attached to the individual”. The early captive airmen who set the tone for every camp escape organisation, however, would have had no way of knowing this, and perhaps did not want to trust to the AOC’s good sense, even if they did.

Fear of being declared LMF—lacking moral fibre—may well have had something to do with it. When I interviewed Cy Borsht, who spent the last months of the war in Stalag Luft III’s Belaria compound, I noticed in his wartime log book a wonderful watercolour of him tunnelling. This was in the post-Great Escape climate and, knowing that even the camp authorities had (ostensibly) supported the German decree of no more escaping or face the deadly consequences, I asked him why he was involved in escape activity. He told me, ‘You know, it’d be considered a bit of a coward’s way out to say “No, thanks, I don’t want to escape”. ‘So there was a certain amount of peer pressure then, really, in that if you said no, you would have felt that they thought you were a coward?’, I asked. ‘Absolutely’, Cy responded.

Courtesy of Cy Borsht

Other factors may have motivated the vaulters, those who kept watch, those who created diversions, those who disposed of the diggings, those who risked much by forging papers and making uniforms despite the knowledge that only a handful would ever make a bid for freedom. There may have been an element of altruism for some, doing something for the common good, or, as Bert Comber and Peter Tunstall believed, an obligation of the active airman to continue operating behind barbed wire by creating as much disruption to the enemy as possible. But I think too, we can never underestimate the power of boredom—the need for ‘something to do’—as a motivating factor.

Lifted from the film, courtesy of my trusty little 21st century version of the box brownie.

In this cinematic representation of life in captivity, there is no doubt that camp life is mind-numbing, claustrophobic, and dreary. The barbed wire and sentry tower are almost the first images the viewer sees. Then there are the sombre looking, pyjama-clad POWs looking out the window at the same old, same old, before dully returning to their bunks. Other kriegies lay sleeping; some look morose in slumber, some are dreaming happy thoughts. One dreams of the crash that took him out of action and into captivity. All are trapped in a crowded room, in a crowded camp and yet they try to imprint a little of their personality on their environment by evoking their former lives. They pin pictures onto the wooden walls: an aeroplane soaring freely in the sky and family photos of wives and children. To reinforce the visual, the first words the viewer hears are not a lively dialogue, but an internal monologue, focussing on the dissatisfaction and monotony of camp life in close quarters: ‘I knew it all so well’, says Peter Howard (Leo Genn)—who represents Eric Williams in the film—as he ‘tensed’ himself in anticipation of the all too familiar morning activity of his bunk mate. The never ceasing routine: ‘breakfast please; you’re cook’; thinly slicing the hunk of bread to make it go round; the grouching man; the call of ‘goon in the block’ as a guard passes through; the communal showers; and parcel day’s anticipation of the prospect of a Red Cross package or much-desired letters from home.

Someone's vision of Red Cross Comforts.

These set pieces are all standard fare when presenting the tedium of captivity as they establish what life was like in a POW camp. But while they show that life was boring and colourless, they also indicate that it was safe and the prisoners were relatively secure. In this world (if not in reality) they do not suffer physical strictures and mental trauma is only hinted at.

This film, as do all in the prisoner-of-war genre, presents another side of captivity. The captive might be out of action, but he is still very much an active airman, albeit behind barbed wire. We see guards who have been suborned by the prisoners. We view the well-rehearsed impertinence towards the guards—‘Deutschland kaput’—and later, the motley crew presenting themselves at appell (roll call) in a mixture of shorts, pyjamas, and uniform oddments: definitely not what you would expect from morning parade at any RAF station in England, but par for the course for active airmen ‘sticking’ it to the Germans. Here we see the active airmen in many guises: the duty stooge, logging in the actions of the ferrets as they try to detect escape activity; the digger emerging from a tunnel, declaring ‘40 feet today’; and Peter Howard and John Clinton (Anthony Steel)—Michael Codner in real life—walking the circuit, and planning another possible scheme.

I’ve mentioned some of the reason for a man’s involvement in escape activity but there was also something deeper, something almost visceral motivating him to risk an authorised exit from the POW camp. ‘This is a hell of a life, Peter’, says Clinton, and Peter Howard would ‘give anything to get out of this place—even if it was only for a few days. Just to do the ordinary things again’; just to enjoy the simple things like a phone call, walking on grass, or even a carpet. The desire for freedom, to run your own life, to fulfil your own desires without constraint, is perhaps the greatest motivator. But so too is the desire to accomplish something in life, and that is why we hear so often of prisoners of war who undertook academic studies to lay foundations for future careers or designed homes of their dreams. The fictional Peter Howard touched on something that disturbed almost every real life prisoner of war: ‘Sometimes I wonder if it’s better or worse for the married chaps—at least you’ve got something waiting for you. I’ve got a feeling that life’s passing me by. By the time I get back it’ll be too late. It’s not doing anything—not even fighting!’

And then, of course, he and Clinton come up with their own fighting plan. No one, of course, can be in any doubt that the Wooden Horse scheme is a military operation. The plan has to be endorsed by the escape committee and Senior British Officer, resources have to be devoted to it, and the whole thing is carried out under military lines. They may have worn pyjamas and shorts on parade, but the night they go scrounging for materials, they wear battle dress. Admittedly the darker clothes make them harder to see, but military dress reinforces that these men are on operations; they are once again active airmen.

One of the hallmarks of the active airman is ‘kriegie ingenuity’. Here, Wing Commander Cameron is the president of the Kriegie Construction Company. Ostensibly, and with full goon approval, he is making an air conditioning plant for the hut in his fully-kitted out work room. But any air conditioning mechanism will find itself co-opted to the latest tunnel scheme, and Cameron’s endorsed carpentry bench will also turn out tunnel supports and other sundry escape aids, including, after a little chat with Peter Howard, a wooden vaulting horse.

Horse in place, all that is needed now, are vaulters. On the face of it, the film appears to present a disconnect with what we think we know about the physical appearance of the prisoners. For instance, we know that German rations were barely adequate and had to be supplemented by Red Cross parcels. We know that meals were eked out by culinary ingenuity and—in times of Red Cross plenty—the prisoners probably had enough calories per day to get by on. They were fit enough and played sport but surely they were far from perfect athletic specimens?

From Cy Borsht's wartime log book, courtesy of Cy Borsht.

Yet, in this film, the vaulters all look fit and healthy; they are portrayed as Adonis types who had no apparent problems with their rations, and who could effortlessly march off the sports ground carrying a man hidden in a wooden horse.

Lifted from the film, courtesy of my trusty little 21st century version of the box brownie.

So perfect were these cinematic versions of the POWs that, apparently, Peter Butterworth, who was one of the real-life vaulters, could not get a part in the film because he looked neither athletic nor heroic enough! But it seems that the film’s vaulters may have correctly depicted the real vaulters as there is pictorial evidence of some agile, healthy-looking athletic types putting on a strong-man gymnastic show in Stalag Luft III in November 1943, just after the real-life wooden horse breakout.

Courtesy of Drew Gordon.

It doesn’t take too much imagination to picture those chaps vaulting all day, with others carting the horse and hidden man around the compound. So, with the film—and photos like this which appeared in one of the pictorial accounts of life in Stalag Luft III—we can well see why some of the reviewers had their doubts about the ‘living death’, and we can well understand why there was a widespread post-war perception (amongst those who were not there), that captivity in Germany was a bit of a doddle.

As we know, the prisoners line up willingly to jump the horse while the diggers dig. The ‘good turnout’ at the beginning is acknowledged, but so too is the probability that that might not be the case in a few weeks’ time. And indeed, the novelty wears off. Howard and Clinton note that they have to get a move on with the digging because they couldn’t have the boys jumping for nothing. But of course, the boys were jumping for nothing as they had no personal stake in this operation; they were vaulting so that someone else could escape, not them. The good will extended beyond the sports ground as those in Howard’s and Clifton’s mess were obliged to take up the housework slack as the diggers time and again missed out on doing their chores. One man, however, embodying quite human resentment, ‘chucked a tanti’ about Clifton not pulling his weight. The solution was that Howard and Clifton would form their own mess. (If they starved, it would be their own fault!) But the scene displayed more than just a disgruntled roommate. It demonstrated that there was a limit to the good-natured cooperation that underpinned this escape effort. All was later forgiven, however. The disgruntled officer handed over some German money to the escapers, as it ‘might come in handy’. But was that an indication that he regretted his earlier behaviour, or was it an acknowledgement that every man had a part to play in an escape attempt—regardless of the costs to the many so that the few could make a bid for freedom—because of what the enterprise represented? Certainly, despite the ongoing difficulty of maintaining the vaulters’ enthusiasm, when things start going wrong, everyone pulls together to ensure success. When one of the jumpers notices a hole created after a partial tunnel fall, he pretends to be injured and another bandages his leg to cover-up the playacting, and the hole is safely repaired. It seems, for the main part, that personal interest was put aside for the benefit of the escapers and, in that, we see a strong element of altruism.

While one of the rationales for escape is the disruption it will cause to the enemy—and this was certainly the case for North Compound’s Great Escape—the cinematic wooden horse venture does not appear to generate much of a hue and cry after the escape of Howard and Clifton, along with Philip Rowe (David Tomlinson)—Oliver Philpot in real life—the third man in the enterprise brought in at a late stage to help speed things along. But the many helpers suffered for their support of the three escapers. While Howard and Clifton are catching their train, the ‘meanwhile-back-at-the-camp’ scene reveals the penalties suffered by those who helped. Weekly showers are stopped, the camp theatre is closed for the duration, all sport is forbidden and, of course, access to the wooden horse is denied. (In an ambiguous conclusion to this segment of the film, the men cheer as the horse is carted away. Are they so sick to the sight of it that they can do little but cheer, or are they acknowledging the successful escape?)

Before I sign off, I want to look at how women are portrayed in this film. For the most part, women were physically absent from captivity. Bill Fordyce, one of the Australian Great Escapers (who was caught in the tunnel when the alert was sounded) once remarked that ‘except for looking through the wire at the German censors, we hadn’t seen a woman for about four years’.

Bill Fordyce

Even so, women were ever present and this film subtly reinforces that women were a significant part of captivity, even in their absence. I mentioned earlier the family photos that adorn the room. The photographic images evoke memories of happier times with wife, girl friend or fiancée. But the chaste life partner was not the only rendition of womanhood in this cinematic version of Stalag Luft III. While taking a shower, the men sing a song declaring they don’t want to go to war, they’d rather stay at home and drink with the daughters of the high born ladies. The poster calling for vaulting volunteers depicts an agile prisoner with wings on his feet, lasciviously chasing a woman in a bikini. ‘Peace in our time? Get fit now!’ exhorts the caption, the unsaid text being so that when you are out of here, you will be fit enough to catch the maiden of your dreams.

Lifted from the film, courtesy of my trusty little 21st century version of the box brownie.

Perhaps surprisingly women actually appear in this film. After they have successfully exited camp, Howard and Clifton purchase their train tickets from a woman.

Lifted from the film, courtesy of my trusty little 21st century version of the box brownie.

Peter Howard might have wanted to escape for the very simple things in life like carpet and grass under his feet, but he was presented with much more in the final scenes of this film: flowers on the tables of a plush restaurant, a smart suit, money and coupons (‘three courses only’) at said plush restaurant, and, as he watchs two uniformed Germans and their female companions looking on disapprovingly, the satisfaction of knowing that he and his friends had stuck it to the Germans. ‘I believe they think we shouldn’t be here’.

The Wooden Horse may be a cinematic rendition of a fictionalised version of a real escape but even so, much of it stacks up well against true accounts of life in Stalag Luft III. It demonstrates that escape is a significant part of captivity for all sorts of reasons and that prisoners of war remained active airmen, still on operations, despite being behind barbed wire. They displayed ingenuity and prided themselves on getting the best of their captors. Significantly, this film also demonstrates that getting the best of the Germans was very much a team effort. Duty was a large part of it, but there were other rationales, including the desire to continue the battle behind barbed wire. And—if you ignore the gratuitous inclusion of women in the post-escape scenes—it indicates that women had a significant and ever present place in the lives of prisoners of war. But The Wooden Horse also reinforces the impression that prisoners of war in Europe had a fairly decent time of it in captivity.

Not to be contradictory, Kristen, but I'm not sure that I agree with your final sentence. While it is true that Air Force officer POWs were, for the most part, well-treated, that cannot be said as a wide-sweeping description of all POWs, especially for non-Air Force NCOs and other ranks. Remember that the Luftwaffe insisted to the German High Command that they be responsible for guarding all Allied Air Force POWs. At the head of the Luftwaffe was Göring, a former World War 1 pilot, who still considered all airmen as "Knights of the Air." As such, the Luftwaffe treated Air Force officer prisoners with a certain deference and chivalry. My understanding is that this was not the case with most other Allied POWs, especially ground troops. Under the terms of the Geneva Convention, officer prisoners could not be forced to work. But NCOs and other ranks could be, and they were, often in agriculture or in forestry. While their labour conditions were not as horrific as those experienced by the captives of the Japanese in the Pacific theatre, they were, nonetheless, not anywhere near as "cushy" as the relatively "easy" circumstances in which Allied Air Force officers found themselves. Marc Stevens, Toronto.

ReplyDeleteHallo Marc, I know that there were many different treatments of airmen NCOs and indeed officers (as well as army and naval personnel) throughout the German system. However, for many reasons - including acknowledgement of greater trauma suffered by those who experienced captivity under the Japanese, and considerable underplaying by both the men themselves and the Red Cross as they attempted to alleviate the stress suffered by families - this created a distinct perception that captivity in Germany was relatively easy. Mackenzie rebuts this 'myth' in his The Colditz Myth. Films such as The Great Escape and The Wooden Horse reinforce the impression.

ReplyDeleteSorry, Kristen, I had come away from your review understanding that you agreed with the "impression". Glad to learn that I was mistaken. While my father probably had as good a treatment as anyone did, he lost 40-50 lbs during his 3 years and 8 months as a POW of the Nazis. Admittedly, about half of that came after the Long March (the last 3 months of the war). But still, he was probably only 160 lbs to begin with, and could ill afford such a drastic weight loss. Marc Stevens

Delete