I recently had the pleasure of being interviewed by author Justin Sheedy. This appeared on his Goodbye, Crackernight blog at http://crackernight.com/2013/07/01/kristen-alexander-author-of-australian-eagles-australians-in-the-battle-of-britain-interviewed-by-fellow-author-justin-sheedy/

Justin very kindly allowed me to republish the interview here. The formatting is not quite the same but the substance is!

Kristen Alexander is the author of Clive Caldwell Air Ace (Allen & Unwin 2006) and Jack Davenport Beaufighter Leader (Allen & Unwin 2009), two definitive biographies of Australians at war which have been received just as warmly by the general reading public as by military history experts.

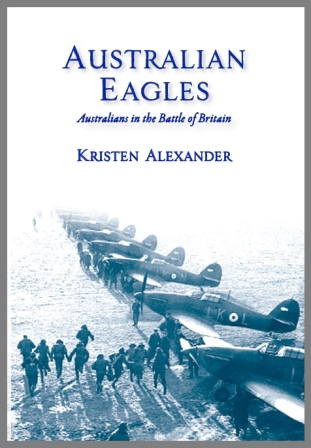

Demonstrating her flair for rich historical detail at the same time as being accessible and easy to read, Kristen’s latest offering, Australian Eagles, Australians in the Battle of Britain has this week been published by Barrallier Books. I was lucky enough to interview Kristen in the lead-up to this highly-anticipated release…

Your literary portraits of Australian air-combat heroes from World War II have been thoroughly enjoyed and widely acclaimed by both Australian and International readers. What are your key inspirations to write about these amazing young men?

I came to Clive Caldwell’s story almost by accident. My husband and I own a second hand book business, specialising in military history. We purchased some letters written by Caldwell during his time in the Western Desert, shortly after his first victories. I read the letters and was fascinated. I wanted to learn something about the man who wrote so freshly, vibrantly and candidly—the letters were to a male friend—about his experiences. I started researching him and decided to do a talk for my military history group. One of my friends said ‘there’s a book there’ and so I continued researching!

Jack Davenport also came about by accident. While writing Clive Caldwell Air Ace I spoke to Peter Ilbery, who had done a lot of research on the Empire Air Training Scheme, as I wanted to clarify some aspects of the scheme. We also talked about Caldwell as a leader and the nature of leadership and Peter, who had served with 455 Squadron during the war, compared Caldwell’s leadership practice with that of 455’s one-time CO Jack Davenport. Sometime after finishing CCAA, aviation author Lex McAulay, who assumed I would continue to research Australian pilots, emailed me a list of possible ‘candidates’. Jack Davenport was on the list. Next thing I knew, Peter was on the phone saying he had heard I was going to write about Jack Davenport. And it seemed I was!

From the start, my Battle of Britain research was something I was consciously drawn to. I had finished Jack Davenport Beaufighter Leader and was reading H.E. Bates’ A Moment in Time, which is set during the Battle of Britain. An Australian was mentioned and I wondered if Australians had really fought in the Battle or if Bates had been exercising some creative licence. It only took a little reading to discover Australians had fought and by that stage I wanted to know more, and from there I set forth on a new research path.

Whatever the original spark, I have concentrated more on writing about the person behind the pilot than the battles in which they fought. I wanted to try and understand what motivated them, what made them a good pilot, and the importance of their relationships with other people. For me, biography is my writing inspiration; the people who make up history. But I still want to get the history right, and so I read a lot about the ‘life and times’ of my subjects so I can set them and their experiences in the historical context.

What qualities from the Australian ‘national character’ would you say made these young Australians stand out on the ‘world stage’ on which they fought?

We are a laid back country but when something gets under our skin passion and commitment flare up. We are willing to fight for a cause and in the Second World War that cause was freedom from tyranny. All my pilots share a love of their country, whether the one in which they were born, or an adopted homeland; a commitment to duty; and a flash of larrikinism or the tendency to go beyond the rules when necessary. They were also loyal to their comrades: mateship, of course, is another very Australian trait.

Just one highly-praised aspect of your works is how you so richly capture the ‘atmosphere of the times’ in which these shining young Australians put their lives on the line to defend Australia and the Free World, often crossing the world to do so. Do you think, given similar circumstances today, that young Australians would do the same en masse as they did in World War II?

I think we would. And plenty already do. Our brave servicemen and women have been fighting in Afghanistan for many years; our peacekeepers continue to make the world a better place; our emergency personnel drop everything to offer their expertise during disasters here and in other countries. We are a nation of volunteers and donators to great causes and we value democracy and a safe world. This commitment to others is a part of the Australian psyche. If our homeland were threatened, we would rise to the challenge just like the young men and women who served in so many capacities during our world wars.

Fighter pilots from World War II even in their own lifetimes achieved a legendary ‘mystique’ with the wider public, an almost ‘super-human’ aura about them by contrast to ‘mere mortals’ like us. And yet these young fighter pilots were human beings just like us. What human qualities do you think characterised these young men given the amazing feats they performed?

They were dedicated to flying. More than that, they were passionate about flying. Clive Caldwell lied about his age and, when he discovered all on his training course would end up as instructors, he finagled his way out of it and into fighter training. Dick Glyde overcame a slight curvature of spine when he was turfed out of the RAAF for medical reasons and applied for the RAF. And when they became pilots, they did all they could to ensure they were the best. Clive Caldwell practised shooting and devised his own technique to perfect his art. John Crossman diligently supervised the maintenance of his Hurricane to ensure it was in tip top condition. And when they were fighting, they let nothing distract them from their duty.

That commitment to duty was the trait that impressed me the most, especially in relation to the Battle of Britain pilots. All of my subjects displayed a commitment to duty but there was a difference. Clive Caldwell and Jack Davenport enlisted knowing they would have to fight but the Battle of Britain pilots did not set out to fight a war. They joined the air force so they could fly. But when war came, they accepted that they would have to fight; it was their duty. John Crossman said it all: ‘Should this last any time it seems unlikely that I’ll ever see home again. Still I expect it can’t be helped. A fellow has to realise that.’ And then he decided to apply for fighter training instead of bomber training, as he had originally planned, so he could take the fight to the Germans.

Your first book, Clive Caldwell Air Ace, was a portrait of Australia’s top-scoring fighter pilot from World War II, your next the warmly received Jack Davenport Beaufighter Leader, portrait of this so very impressive Australian bomber pilot. What would you say are the key personality differences between these two different breeds, fighter pilot / bomber pilot?

Clive Caldwell and Jack Davenport were remarkable men who achieved great things in war and peace. I think the key difference between them as fighter pilot and bomber pilot was that Clive Caldwell was an individualist—he was accused of being a lone wolf by his squadron—which made him a good combat pilot. He could accept risks to his own safety; he wasn’t responsible for any other man. Jack Davenport wanted to be a bomber pilot from the beginning because he felt a responsibility to others, and he was willing to accept that. He was what we would now call a team player; operations aside, his crew would always come first. And that’s what made him a good bomber pilot and crew leader.

Both were touched by war but those experiences left very different legacies. I think the main reason for such different reactions to the war can be seen in the nature of their service. As a fighter pilot, Caldwell was solely responsible for himself and his actions. In aerial combat, he looked into the whites of his enemies’ eyes, so to speak, and he saw his comrades fall in battle, sometimes in flames, or shot down as they parachuted from their aircraft. He saw upturned faces of the perhaps still living Japanese aircrew. He was wounded in battle at least once. Death for him was an almost intimate experience. As a bomber and anti-shipping pilot, Jack Davenport, like Caldwell, encountered danger on each sortie but he was more removed from the enemy. He dropped his bombs in darkness on cities often obscured by smog haze. He fired torpedoes, cannons and rockets at huge merchant ships whose anti-aircraft defences were firing directly at him. He may have seen their bodies blown off the vessels, but he did not see faces of the flak operators or enemy sailors. They did not return to haunt him. And rather than dwell on the long ago encounters, he eschewed inward contemplation of his role in warfare. He turned his attention outwards, towards others.

Your next release is Australian Eagles, Australians in the Battle of Britain. What can readers expect from this, your latest offering?

More biography! Though this time I look at the lives and flying careers of six airmen. Australian Eagles is a collection of six biographical essays. It has been solidly researched but it is perhaps more accessible to a broader readership than my first two books in that I don’t interrupt the flow of the story with references. Other than some brief introductory material, I don’t retell the story of the Battle of Britain. I just focus on the place ‘my’ boys had in the Battle. Because the majority of the essays were originally published in Wings, the RAAF Association’s magazine, they are short biographies that can be read in one sitting. The simpler storytelling is a different approach for me and the essay form meant I had to focus on key aspects of ‘my’ pilots’ lives. In addition to Jack Kennedy’s, Dick Glyde’s, John Crossman’s and Des Sheen’s stories which were originally published in Wings, Australian Eagles includes Stuart Walch’s and James Coward’s stories, which I have not published before. And because I could not help myself, I have added new information to all the Wings stories.

The book is beautifully produced on quality paper with lots of photos. I have signed and numbered each one of the collectors’ edition of 500 copies. I am very proud of Australian Eagles.

Ever since Winston Churchill coined his legendary rhetoric, the Battle of Britain has been mythologised as Britain and the Commonwealth’s ‘finest hour’. Given your intense labour of research in writing Australian Eagles, what would you say might have been the Battle’s ‘finest hour’?

I think the Battle of Britain produced many fine hours: The moment when the pilots committed to a possible death in battle when all they had wanted to do in the first place was fly. The moment when a fighter pilot became embroiled in deadly a dogfight and twisted and turned until he could line up in his sights another aircraft, flown by a man perhaps as young as he. And then fire. The moment when the British people decided to thumb their noses at Hitler and not succumb to the threat of a possible invasion or to give up under bombardment. Britain can take it. She certainly could. There are too many fine hours to pinpoint just one.

If the young Allied pilots were the heroes of the Battle of Britain, it might be said that the ‘heroines’ were the fighter aircraft they flew: The legendary Spitfire and Hurricane. In the ensuing 73 years since the Battle was won, much has been written about these two aircraft, and to this day there exists divided preference as to which was the greater in terms of their contribution towards ultimate victory in the Battle. Which would you nominate as the greater and why?

I’m not falling into that trap! Both aircraft had their vices and virtues. Flown with skill and daring, they were both lethal weapons. The Spitfire and Hurricane were not the only heroines of wartime. We mustn’t forget the women who waited for their men to come back: the Jean Caldwells in Australia who feared the arrival of a telegram and the Sheila Davenports in the United Kingdom who dreaded a call from the Station Commander after an op, but who ultimately welcomed their husbands home, and the Pat Foleys who had no idea when their fiancés would return and then received the cruel telegram advising a tragic death. They were true heroines.

As a result of the limited gender perceptions that prevailed in the World War II era, only young men were ever considered as capable of becoming fighter pilots. As a female author with more passion for and detailed knowledge of the era than most men, have you ever dreamed of being a Spitfire pilot?

Oh no. My passions lie elsewhere. I leave it to ‘my’ boys to experience the joy of flight in Spitfire, Hurricane, Kitty Hawk or Beaufighter. I don’t feel that I am at a disadvantage as an author of aviation biography in not being a pilot. From the beginning, I have wanted ‘my’ boys to tell their stories in their own words. I am just the conduit for them to have their say. Where possible, I draw on their own flying experiences through letters, diaries and other written works, combat report and interviews. After all, any experience I have would be very different from theirs!

What are the most important messages that you would hope readers take away from reading Australian Eagles, Australians in the Battle of Britain? What is THE most important?

That Australians did indeed participate in the Battle of Britain, that they fought well, and bravely. That some gave their lives to protect the freedom of others and that their sacrifice is remembered. Perhaps the most important message is that they ARE remembered.

Australian Eagles, Australians in the Battle of Britain by Kristen Alexander is now available. You can purchase Australian Eagles (ISBN 9780987414229) as well as Clive Caldwell Air Ace and Jack Davenport Beaufighter from www.alexanderfaxbooks.com.au (which is owned by Kristen and her husband David). All copies will be signed.

When ordering, please let Kristen know if you would like a personal message.

If you prefer to load up your ereader, you can obtain the

ebooks via amazon http://www.amazon.com/Clive-Caldwell-Air-Ace-ebook/dp/B0051SIUX0/ref=sr_1_1_title_0_main?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1369553196&sr=1-1&keywords=clive+caldwell+air+ace

Connect with Kristen at:

Interviewer, Justin Sheedy, is the author of Goodbye Crackernight, a comic memoir of growing up in 1970s Australia, and of Nor the Years Condemn, an historical fiction based on the stunning (and untold) true story of the young Australians who flew Spitfires in World War II. See Sheedy’s interview with Kristen at http://crackernight.com/2013/07/01/kristen-alexander-author-of-australian-eagles-australians-in-the-battle-of-britain-interviewed-by-fellow-author-justin-sheedy/

“Goodbye Crackernight” is available at Dymocks, also as an Ebook and in paperback at Amazon. “Nor the Years Condemn” is available at Dymocks, in paperback at Amazon and as an Ebook at Smashwords.

And now at Gleebooks, Berkelouw Books Paddington and The Australian War Memorial. Sheedy’s latest book, Ghosts of the Empire (much-anticipated Sequel to “Nor the Years Condemn”) will be released at the end of July 2013.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment